Psychologist Clayton Alderfer’s E.R.G. motivational theory of human behaviour offers marketers a potential framework for charting steps forward in uncertain times – Nanyang Business School’s Mansur Khamitov talks through how brands can map out a positive path forward.

The likelihood of new behaviours and lifestyle norms/patterns formed during the outbreak sticking once things return to “normal” is quite high.

Brands should be mindful of any signals or displays arising from their communication efforts which may be viewed as encroaching or otherwise compromising the fundamental safety and security of their customer base.

One of the most successful recovery strategies are those that enable consumers to “heal” and rebuild. This article is part of a special WARC Snapshot focused on enabling brand marketers to re-strategise amid the unprecedented disruption caused by the novel coronavirus outbreak.

Read more.

While the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) situation is still far from reaching its peak and continues to disrupt brands’ ambitions and plans, there are certain classic theories and frameworks that can offer some guidance in the post-coronavirus era. Thinking beyond the current predicament, when things return to relative normalcy, where does that leave brands and their 2020 ambitions?

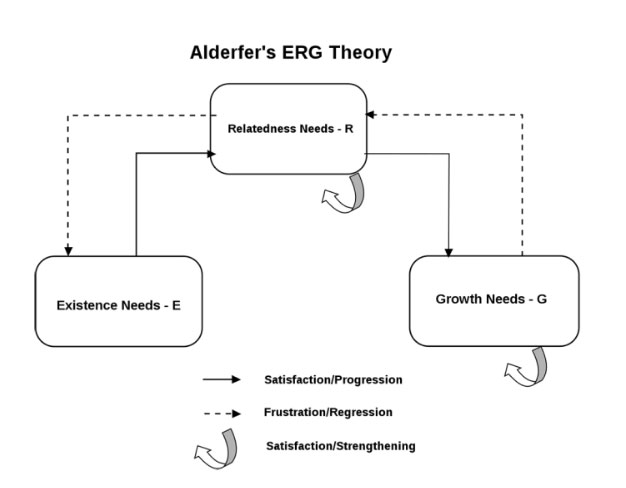

One such framework that can be fruitfully applied is the E.R.G. motivational theory of human behaviour, developed by a psychologist Clayton Alderfer in his seminal Organisational Behavioural and Human Performance article. The framework is based on a three-fold conceptualisation of basic underlying human needs: existence, relatedness, and growth. While existence needs include all kinds of required basic material, safety and physiological desires, relatedness encompasses needs which involve the desire people have for establishing and maintaining important interpersonal and social relationships.

While it does categorise needs into lower-order ones (e.g. physiological- and safety-based existence needs) and higher-order ones (e.g. growth needs related to personal development), the critical difference between this and other popular needs-based frameworks like the one by Maslow is that E.R.G. does not assume lower-level need satisfaction as a prerequisite for the emergence of higher-order needs. Hence, it offers a more realistic account where multiple needs dynamically co-exist and interact.

Applying this framework highlights several notable takeaways for brands and marketers moving forward. The first phase lies in understanding the impact of this unprecedented chain of events on consumer behaviours:

Changing desirability of relatedness

The first pattern that surfaced can be traced to the risks of today’s ever-connected mobile and sharing economy. Increased globalisation and excitement about all-things shareable sought to increase social capital, boost community, enable meeting new people, build trust (including “stranger” trust), and foster social inclusivity.

Somewhat ironically, flagship global airlines were among the first to feel the heat with some notable players like Cathay Pacific and Asiana Airlines letting a number of their employees go on unpaid leave while encouraging their staff and passengers to reduce interactions, limit public activities, and practice social distancing. Relatedly, Grab Share was one of the first suspended options in Singapore – leading people to wonder whether and when the feature would be coming back.

While this move by Grab elicited somewhat mixed consumer reactions including understandable urges to avoid panic, many individuals were fast to praise the move on online forums along the lines of “Good call Grab!”, “No more sharing economy?!”, or “Please stop ALL Grab services immediately!”. Some even went as far to say “If [you] ban Grabshare, then ban MRT and buses also. What’s the difference between people together in a car and people together on the train/bus?”

Taken together, this signals changing desirability of relatedness and highlights that in a context like this, social interactions, interpersonal connections and mingling, while otherwise typically desirable, may backfire. While it takes years, multiple touchpoints, and numerous efforts to build up reputation, people are quite fast to rush to conclusions when it comes to perceived protection and safeguarding of their basic security and safety needs, and any seemingly infallible brand and its reputation can be dealt a major blow within a short span of time.

Therefore, given the changed state of desirability of relatedness, brands should be mindful of any signals or displays arising from their communication efforts which may be viewed as encroaching or otherwise compromising fundamental safety and security of their customer base.

A reprioritisation of needs

One notable development is how many people have become considerably less materialistic, possessions oriented, and status-driven. Notably, luxury and non-necessity brands suffer the most during such situations. Burberry, Gucci, Saint Laurent, Alexander McQueen Michael Kors, Versace Jimmy Choo, Coach, Kate Spade, Stuart Weitzman and the like all slashed their forecasts and cut back on their ambitions as reported in a recent piece by the New York Times.

Unsurprisingly, the global luxury goods sector is bracing for impact not only because of lack of tourists or store closures but also, and importantly, because of lower foot traffic among locals. This opens up a clear and compelling possibility for non-luxury segments to tap into this reprioritisation of needs. While temporarily foregoing luxury and discretionary pursuits in favour of basic necessities would be logically predicted by E.R.G. theory, once it’s all over I won’t be surprised if there’s a resurgence of luxury brands, with people rewarding themselves and their loved ones for having underwent the crisis and coping with the waves of relative uncertainty.

To best prepare themselves, luxury brands may already want to start crafting their campaign messages, drawing attention to how their customers and their loved ones have grown both emotionally and psychologically and how they symbolically deserve to be rewarded as a result.

Emerging new lifestyle norms

Proliferation of e-commerce, online grocery shopping and delivery, automation, virtual classrooms, teleworking and AI-enabled healthcare is here to stay. Enabling and facilitating existence needs related to safety, security and physiology have increasingly come to the forefront and are widely seen as taking their rightful place.

Planning the path to recovery and normalcy

Adopting a forward-looking perspective, it would be important for brands to send a resilience-type message wherein brands that walk the talk to rebuild communities and help society bounce back in the aftermath would be the ones to benefit.

The optimal brand tone derived from the E.R.G. framework would be to display that you care, are empathetic, and at the same time are here for consumers to move on with their everyday lives, fast-tracking temporarily foreshadowed satisfaction of growth and relatedness needs beyond pursuit of basic existence needs.

Having said that, this is a little bit complicated and sort of a grey zone for brands, requiring very careful and gentle navigation. If you don’t talk about it, or at the very least acknowledge it somehow, you risk appearing indifferent and cold. However, if you do talk about it, you risk appearing insensitive, trying to take advantage, and/or alienating a certain portion of your customer base.

As a case in point, my own research on negative events suggests that one of the most common grievances consumers have with brands are those where consumers feel that their personal values and freedoms have been violated while one of the most successful recovery strategies are those that enable consumers to “heal” and rebuild. Some recent examples of how brands may successfully take on a very active community recovery role are the likes of Alibaba, JD.com, and Tencent in the evolving Covid-19 situation.

They appear to have been instrumental in temporarily or permanently taking in thousands of impacted and displaced workers, providing or funding community guidance apps and programs including elements of counselling, investing into tech solutions to accelerate future emergency responses, helping people get back to work and school (whether physically or virtually) as well as re-establishing compromised supply chains.

Brands may be powerless to stop crises from happening, but they can certainly do more to help people stay positive, optimistic, and forward-looking. If you as a brand treat customers and clients graciously during the crisis and its aftermath, don’t be surprised when they stick with you when normalcy returns.

Focusing on the “heal and rebuild” angle, recent research findings by a colleague of mine at Nanyang Business School suggest that even post-outbreak, people in affected countries (and particularly in high-density cities) are likely to remain stressed and frustrated. One way for brands to restore their sense of equilibrium is by enabling such individuals to exert control in their own lives by buying practical, utilitarian products.

Sources

- Alderfer, Clayton P. (1969), “An Empirical Test of a New Theory of Human Needs,” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4 (2), 142-175.

- Khamitov, Mansur, Khamitov, Mansur, Yany Grégoire, and Anshu Suri (2020), “A Systematic Review of Brand Transgression, Service Failure Recovery and Product-Harm Crisis: integration and Guiding Insights,